Who Was Beyonce's Parents What What Did They Name Their Baby

T im Foley turned xx on 27 June 2010. To gloat, his parents took him and his younger brother Alex out for dejeuner at an Indian restaurant non far from their abode in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Both brothers were built-in in Canada, just for the past decade the family had lived in the U.s.a.. The boys' male parent, Donald Heathfield, had studied in Paris and at Harvard, and at present had a senior role at a consultancy firm based in Boston. Their mother, Tracey Foley, had spent many years focused on raising her children, earlier taking a job as a real estate agent. To those who knew them, they seemed a very ordinary American family unit, albeit with Canadian roots and a penchant for foreign travel. Both brothers were fascinated by Asia, a favoured vacation destination, and the parents encouraged their sons to be inquisitive nigh the world: Alex was only 16, but had simply returned from a six-calendar month student substitution in Singapore.

After a cafe lunch, the four returned dwelling house and opened a canteen of champagne to toast Tim reaching his 3rd decade. The brothers were tired; they had thrown a small house party the nighttime earlier to mark Alex's return from Singapore, and Tim planned to get out later. After the champagne, he went upstairs to message his friends well-nigh the evening'due south plans. At that place came a knock at the door, and Tim's mother chosen up that his friends must have come early, every bit a surprise.

At the door, she was met by a different kind of surprise birthday: a squad of armed, black-clad men holding a battering ram. They streamed into the house, screaming, "FBI!" Another team entered from the back; men dashed up the stairs, shouting at everyone to put their hands in the air. Upstairs, Tim had heard the knock and the shouting, and his starting time thought was that the police force could exist after him for underage drinking: nobody at the political party the night before had been 21, and Boston police force took booze regulations seriously.

When he emerged on to the landing, it became articulate the FBI was here for something far more serious. The two brothers watched, stunned, as their parents were put in handcuffs and driven away in separate black cars. Tim and Alex were left backside with a number of agents, who said they needed to begin a 24-60 minutes forensic search of the home; they had prepared a hotel room for the brothers. One of the men told them their parents had been arrested on suspicion of being "unlawful agents of a strange government".

Alex presumed there had been some mistake – the wrong house, or a mix-up over his father's consultancy work. Donald travelled frequently for his job; maybe this had been confused with espionage. At worst, perhaps he had been tricked by an international customer. Even when the brothers heard on the radio a few days later that 10 Russian spies had been rounded up across the U.s., in an FBI operation dubbed Ghost Stories, they remained sure there had been a terrible error.

But the FBI had not made a error, and the truth was so outlandish, information technology defied comprehension. Non only were their parents indeed Russian spies, they were Russians. The man and adult female the boys knew as Mom and Dad really were their parents, just their names were non Donald Heathfield and Tracey Foley. Those were Canadians who had died long agone, as children; their identities had been stolen and adopted by the boys' parents.

Their existent names were Andrei Bezrukov and Elena Vavilova. They were both built-in in the Soviet Marriage, had undergone training in the KGB and been dispatched abroad as function of a Soviet programme of deep-cover secret agents, known in Russia as the "illegals". Later on a dull-burning career building up an ordinary North American background, the pair were now agile agents for the SVR, the foreign spy agency of modern Russian federation and a successor to the KGB. They, along with eight other agents, had been betrayed by a Russian spy who had defected to the Americans.

The FBI indictment detailing their misdeeds was a catalogue of espionage cliches: dead drops, brush-pasts, coded messages and plastic bags stuffed with crisp dollar bills. The footage of a airplane carrying the 10 touching downwards at Vienna airport, to be swapped for four Russians who had been held in Russian prisons on charges of spying for the west, brought back memories of the cold state of war. The media had a field day with the Bond-girl looks of 28-year-old Anna Chapman, one of two Russians arrested not to take pretended to be of western origin; she worked every bit an international manor agent in Manhattan. Russia didn't know whether to exist embarrassed or emboldened: its agents had been busted, simply what other country would call up of mounting such a complex, slow-baste espionage operation in the first identify?

For Alex and Tim, the geopolitics backside the spy swap was the to the lowest degree of their worries. The pair had grown up equally ordinary Canadians, and now discovered they were the children of Russian spies. Alee of them was a long flight to Moscow, and an even longer emotional and psychological journeying.

N early on 6 years since the FBI raid, I run across Alex in a cafe well-nigh the Kiev railway station in Moscow. He is now officially Alexander Vavilov; his brother is Timofei Vavilov, though many of their friends yet utilize their sometime surname, Foley. Alex is 21, his nonetheless-adolescent looks start by a serious manner and pragmatic dress: black V-neck over a crisp white shirt. A gentle North American lilt and the conscientious aspiration of concluding consonants give him the unplaceable emphasis of those who accept been schooled internationally – in Paris, Singapore and the US. These days, he speaks plenty Russian to order lunch, simply is past no means fluent. He is studying in a European city and is here to visit his parents; Tim works in finance in Asia. (In the interests of privacy, both brothers have asked me non to reveal details about their working lives.)

Since 2010, they have made a conscious decision to avert the media. They have agreed to talk to me now, Alex explains, because they are fighting a legal battle to win dorsum their Canadian citizenship, stripped from them six years ago. They believe it is unfair and illegal that they are expected to answer for the sins of their parents, and accept decided to tell their story for the first time.

As we eat khachapuri, a Georgian bread stuffed with gooey cheese, Alex recalls the days later the raid. He and Tim stayed up until the early on hours in the hotel room the FBI had provided, trying to understand what was going on. When they went habitation the side by side day, they establish every slice of electronic equipment, every photograph and document had been taken. The FBI'south search and seizure warrant lists 191 items removed from the Foley/Heathfield residence, including computers, mobile phones, photographs and medicines. They even took Tim and Alex's PlayStation.

News crews held a vigil outside; the brothers sat inside with the blinds drawn, their phones and computers confiscated. Early next morning Tim snuck out to get online at the public library and try to observe a lawyer for his parents. All the family unit bank accounts had been frozen, leaving the boys with only the money they had in their pockets and whatever they could borrow from friends.

FBI agents drove them to an initial court hearing in Boston, where their parents were informed of the charges. There was a brief meeting with their mother inside jail. Alex tells me he did not ask her what she and his father were accused of. This seems surprising, I say: surely he must have been dying to ask?

"Here'southward the thing: I knew that if I was going to bear witness in court, the less I knew, the ameliorate. I didn't want to cloud my opinion with annihilation. I didn't want to ask questions, because it was obvious people were listening," he says. A bouncy group of women are celebrating a birthday at the side by side table, and he raises his voice. "I refused to let myself exist convinced they were actually guilty of anything, considering I realised the case would probably describe on for a long time. They were facing life in prison, and if I was to testify, I would take to completely believe they were innocent."

The family had been planning a month-long summer break in Paris, Moscow and Turkey; their mother told them to escape the media circus and wing to Russia. Subsequently a stopover in Paris, Alex and Tim boarded a plane to Moscow, unsure of what to look on arrival. They had never been to Russia before. "It was a actually terrifying moment," Alex recalls. "Yous're sitting on the plane, you lot take a few hours to kill and you don't know what'southward coming. You but sit down in that location and recall and think."

Equally the brothers disembarked, they were met at the plane door past a group of people who introduced themselves in English as colleagues of their parents. They told the brothers to trust them, and led them outside the final to a van.

"They showed u.s.a. photos of our parents in their 20s in compatible, photos of them with medals. That was the moment when I thought, 'OK, this is real.' Until that moment, I'd refused to believe any of it was true," Alex says. He and Tim were taken to an apartment and told to make themselves at home; i of their minders spent the next few days showing them around Moscow; they took them to museums, even the ballet. An uncle and a cousin the brothers had no idea existed paid a visit; a grandmother likewise dropped by, only she spoke no English language and the boys not a discussion of Russian.

Information technology would be a few days earlier their parents would arrive, having admitted at a court hearing in New York on viii July that they were Russian nationals. An commutation was already in the offing, and they arrived in Moscow, via Vienna, on 9 July, all the same wearing the orangish prison house jumpsuits they had been given in America. My face must give away some of my amazement: how does a 16-year-onetime process such an extraordinary plow of events?

Alex smirks at me wryly. "Typical high schoolhouse identity crunch, right?"

Alex and Tim'south father was born Andrei Olegovich Bezrukov, in Krasnoyarsk region, in the heart of Siberia. Since his return to Moscow in 2010, he has given just a handful of interviews to Russian media outlets, mainly apropos the more contempo work he has done as a geopolitical analyst. Details of his past, or that of his married woman, Elena Vavilova, are deficient.

Alex tells me what he knows about his parents' recruitment, based on the little they have told him: "They got recruited into it together, equally a couple. They were promising, young, smart people, they were asked if they wanted to help their country and they said yeah. They went through years of training and preparing."

None of the 10 deportees has spoken publicly well-nigh their mission in the United states of america, or their training past the SVR or KGB. Department South, which runs the illegals programme they were on, was the virtually secretive role of the KGB. One erstwhile "illegal" tells me his training in the late 1970s included 2 years in Moscow with daily English lessons, taught by an American woman who had defected. He was likewise trained in other basics such as communicating in code and surveillance. All the training was done on a one-to-i basis: he never met other agents.

The program was the only i of its kind in international espionage. (Many assumed it had been stopped, until the 2010 FBI swoop.) Many intelligence agencies use agents operating without diplomatic cover; some have recruited second-generation immigrants already living abroad, merely the Russians have been the only ones to train agents to pretend to be foreigners. Canada was a mutual place for the illegals to go, to build up their "fable" of existence an ordinary western citizen before being deployed to target countries, often the The states or Britain. During Soviet times, the illegals had two main functions: to assistance in communications between embassy KGB officers and their US sources (an illegal would be less likely to be put under surveillance than a diplomat); and to exist sleeper cells for a potential "special menstruum" – a war between the US and the Soviet Union. The illegals could then bound into activity.

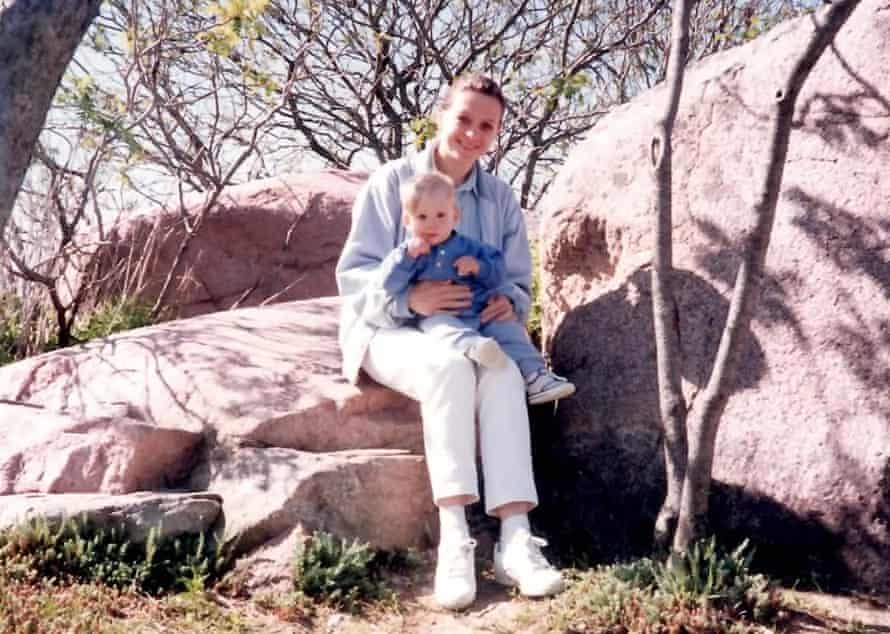

The KGB sent the couple to Canada in the 80s. In June 1990, Vavilova, under the assumed identity of Tracey Foley, gave nativity to Tim at the Women's College hospital in Toronto. His beginning memories are of attending a French-language school in the urban center and visiting the warehouse of his dad's company, Diapers Direct, a nappy commitment service. It was hardly James Bond, but the work of an amanuensis has always been more tortoise than hare – years spent painstakingly building up the legend.

Andrei Bezrukov already had a degree from a Soviet university, only "Donald Heathfield" had no educational records. Between 1992 and 1995, he studied for a available'due south degree in international economic science at York Academy in Toronto. In 1994, Alex was born; a twelvemonth later the family moved to Paris. We don't know whether this was on the orders of the SVR, but it seems a safe supposition. Donald studied for an MBA at the École des Ponts and the family unit lived frugally in a pocket-size flat non far from the Eiffel Tower; both brothers shared the merely bedroom while the parents slept on the sofa.

As Bezrukov and Vavilova built upwards their story, the country that had recruited and trained them ceased to exist. The ideology of communism had failed; the fearsome spy bureau that had dispatched agents across the globe was discredited and renamed. Under Boris Yeltsin, mail service-Soviet Russia seemed on the verge of becoming a failed state. But in 1999, equally the family planned a movement from France to the US, a new man entered the Kremlin who himself had a KGB background. In the subsequent years, he would work to make the KGB'southward successors important and respected again.

With the legend of a hardworking, well-educated Canadian perfected over the years, Heathfield got into Harvard University's Kennedy Schoolhouse of Government towards the end of that twelvemonth, and was gear up to deploy as an agent of the SVR. He would be spying not for the Soviet organisation that had trained him, merely for the new Russia of Vladimir Putin.

Heathfield and Foley sent their sons to a bilingual French-English school in Boston, so they could maintain their French and stay in touch with European civilization. They could not teach their children near Russian federation; perhaps the emphasis on French was a way of ensuring their children were not "ordinary" Americans without ringing alarm bells. At home, the family unit spoke a mixture of English and French. (An online video of Bezrukov, actualization in his post-deportation part as a political analyst, shows him speaking shine North American with the faintest of twangs.) When he completed his postgraduate degree at Harvard, Heathfield got a chore working for Global Partners, a business development consultancy.

I speak to Tim on a Sun afternoon, talking to me on Skype from his kitchen. He has the aforementioned facial features and conscientious departing every bit his younger blood brother, just his pilus is blond rather than nighttime. Looking back on his youth, he tells me his father worked hard, making frequent business trips. He encouraged his sons to read and brainwash themselves about the world, and "was like a best friend to us". Foley, Tim says, was a "soccer mom", picking her sons upwardly from school and taking them to sports do. When the boys were in their teens, she started work every bit a real estate agent.

In 2008, Tim got a place at George Washington University, in DC, to study international relations. He focused on Asia, taking Mandarin lessons and spending a semester in Beijing. The same year, the family became naturalised Americans, with US passports in addition to their Canadian nationality.

The brothers would never alive in Canada again; Alex had been one when they left Toronto and Tim simply five – but both felt Canadian. The family returned often to ski, and when the boys went on schoolhouse trips from Boston to Montreal, they took pride in showing the other students effectually their "dwelling house" land. Alex made a large fuss about his Canadian background, because "at loftier school you always desire to get counterculture".

Tim describes their childhood as "absolutely normal": the family unit was close and spent time together at weekends; his parents had many friends. He has no recollection of them discussing Russia or the Soviet Union; they never ate Russian food, and the closest Tim says he came to a Russian was a polite boy from Republic of kazakhstan at school.

Their parents did not discuss their childhood much, just this was how they had ever been and the boys had little reason to question information technology. "I never had annihilation close to a suspicion regarding my parents," Alex says. In fact, he oftentimes felt disappointed by how boring and mundane they were: "It seemed all my friends' parents led much more exciting and successful lives."

Little did he know. Bezrukov and Vavilova had been put under FBI surveillance soon afterward they moved to the Us, probably because of a mole in the Russian bureau. Excerpts from their 2010 indictment suggest the couple lived with a level of intrigue well-nigh people would assume exists only within the pages of a spy novel. One paragraph recounts an intercepted advice from Moscow Centre (SVR headquarters), explaining how Vavilova should program for a trip back to her motherland. She was to wing to Paris and take the railroad train to Vienna, where she would pick upward a false British passport. "Very important: 1. Sign your passport on page 32. Railroad train yourself to be able to reproduce your signature when necessary… In the passport yous'll become a memo with recommendation. Pls, destroy the memo after reading. Exist well."

Their father, meanwhile, was using his work as a consultant to penetrate U.s. political and business circles. It is non clear whether he managed to access classified material, just FBI intercepts reported a number of contacts with former and current American officials.

In the few public remarks Bezrukov has fabricated about his task, he makes it sound more like that of a thinktank analyst than a super-spy. "Intelligence work is non nearly risky escapades," he told Proficient magazine in 2012. "If yous behave like Bond, yous'll last half a day, mayhap a 24-hour interval. Fifty-fifty if in that location was an imaginary safe where all the secrets are kept, past tomorrow half of them volition be outdated and useless. The best kind of intelligence is to sympathize what your opponent will retrieve tomorrow, non notice out what he thought yesterday."

Bezrukov and Vavilova communicated with the SVR using digital steganography: they would post images online that contained messages hidden in the pixels, encoded using an algorithm written for them by the SVR. A message the FBI believes was sent in 2007 to Bezrukov past SVR headquarters was decoded equally follows: "Got your annotation and bespeak. No info in our files virtually Eastward.F., BT, DK, RR. Agree with your proposal to use 'Farmer' to start edifice network of students in DC. Your relationship with 'Parrot' looks very promising as a valid source of info from US ability circles. To start working on him professionally we need all bachelor details on his background, current position, habits, contacts, opportunities, etc."

Style dorsum in 2001, virtually a decade before her abort, the FBI had searched a rubber-deposit box belonging to Tracey Foley. There they found photographs of her in her 20s, one of which bore the Cyrillic imprint of the Soviet company that had printed it. The family habitation had been bugged, possibly for many years. The FBI knew the couple's real identities, even if their own children did not, but the Americans preferred to keep an middle on the Russian spy band, rather than brand a motility.

Why the FBI finally acted is unclear. One proposition is that Alexander Poteyev, the SVR officeholder believed to have betrayed the group, felt his embrace was blown. He reportedly fled Russian federation in the days before the arrests; in 2011, a Russian court sentenced him to 25 years in prison for treason in absentia. Another possibility is that i of the group was getting close to sensitive information. Any the reason, in June 2010 the FBI decided to wrap upwardly Functioning Ghost Stories and bosom the Russian spy band.

I speak to Tim and Alex many times, in person, over Skype and email. They are not uncomfortable talking virtually their experiences, but neither practice they relish it much. Initially, they want to speak only most their court case in Canada; but gradually they open up up, answering all my questions about their boggling family life.

I have to admit there are some details that carp me. Did they actually never suspect a thing?

In 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported that unnamed United states officials claimed an FBI problems placed at the family's Boston home had picked up the parents revealing their truthful identities to Tim long before the arrest. Furthermore, the officials said, his parents had told Tim they wanted to groom him as a Russian spy. A second-generation spy would exist a much more than impressive asset than first-generation illegals, who had built up personas that were solid but not impregnable to background checks. Tim, according to the unnamed officials, agreed he would travel to Moscow for SVR training and even "saluted Mother Russian federation".

Tim strenuously denies the story, insisting it was a full fabrication. "Why would a kid who grew upwards his whole life believing himself to be Canadian, decide to run a risk life in prison for a country he had never been to nor had any ties to? Furthermore, why would my parents take a similar take a chance in telling their teenage son their identities?"

The claim that he saluted Mother Russia is "just as ridiculous every bit it sounds", Tim says. He would be happy to reply the allegations in courtroom, simply it is impossible to argue with anonymous sources. When contacted by the Guardian, the FBI declined to comment on the Wall Street Journal article.

There was some other thing that bothered me: was it really just coincidence that the family unit had planned to travel to Russia that summer, and that the brothers therefore had Russian visas? Yes, Alex says. "It was very much my idea to go to Russia. We had this world map at home and when y'all looked at the pins on information technology, you could see we'd been almost everywhere just Russia, and so I was very curious and I was pushing for it. It was just going to exist one role of our summer trip."

In hindsight, surely, that summer trip to Paris, Turkey and Moscow must accept looked rather unlike. When the family were reunited in Moscow in July 2010, did the boys ask their parents what the plan had been? Had they intended to reveal everything? Or were they really going to spend a week in Moscow pretending not to sympathise a give-and-take spoken effectually them?

"I really think that was the plan," Alex says. "That we would travel to Russian federation, and maybe they might go and run into people without us. Simply I don't remember there was a plan to tell us anything."

Tim agrees. If their parents had revealed the truth, it would have made Tim and Alex a huge liability; "every bit professionals", he says, information technology's unlikely they would take taken the gamble. They uncertainty their parents ever planned to tell them nigh their existent identities. "Honestly," Tim says, "I actually don't think so. Information technology sounds strange, merely yep."

Both brothers tell me they call up, as young children, seeing their grandparents. Where? On vacation, Alex says, "somewhere in Europe"; he can't remember where, exactly. Asked if he was sure the people he met were his existent grandparents, he says, "I think so." Were they speaking Russian? "I was actually young, I take no idea," he says firmly.

I raise the question with Tim, who would have been older. He remembers seeing his grandparents every few years until he was effectually eleven, when they disappeared from his life. "Obviously, now when I remember dorsum on it, I kind of empathize how it worked. If I had seen them when I was older, I would have realised that they don't speak English – they don't seem very Canadian."

At Christmas, the boys would receive gifts marked "from grandparents". Their parents told them they lived in Alberta, far from Toronto, which was why they never saw them. Occasionally, new photographs would go far of the grandparents confronting a snowy backdrop; information technology helped that the climates of Alberta and Siberia are non so different.

If Tim and Alex'southward story sounds eerily familiar to fans of The Americans, the television drama near a KGB couple living in the US with their two children, that's considering it'south partly based on them. The show is ready in the 1980s, providing a cold war properties, but the 2010 spy round-up served as an inspiration. The prove's creator, Joe Weisberg, trained to exist a CIA example officeholder in the early 1990s and, when I speak to him on the phone, tells me he always wanted to put family at the heart of the plot. "I of the interesting things I saw when I worked at the CIA was people lying to their children. If you have young children, y'all tin can't tell them y'all piece of work for the CIA. And so, at some betoken, you have to selection an age and a time, and they detect out that they've been lied to for most of their lives. It'southward a difficult moment."

When I encounter Alex in Moscow, he has just finished watching the outset season. (He had started on previous occasions, just found it too hard; he and Tim joked that they should sue the creators.) His parents like the evidence, he tells me. "Manifestly it's glamorised, all this killing people and activity everywhere. Simply it reminded them of when they were young agents, and how they felt nigh existence in a foreign new place." Watching it, Alex says, has made him more curious: what set his parents off on this path, and why?

I n 2010, the spies were welcomed dorsum to Russia every bit heroes. Later a debriefing at SVR headquarters, Bezrukov, Vavilova and the other deportees met with then-president Dmitry Medvedev to receive medals for their service. Later, they met with Putin, and the group reportedly sang the patriotic Soviet song From Where The Motherland Begins. The authorities put on a tour: the agents and their families travelled to St Petersburg, Lake Baikal in Siberia and Sochi on the Blackness Ocean. The idea was to show off modern Russian federation, and to provide them with an opportunity to bond.

Do they still meet upward, I inquire Alex. "From time to time," he says. He and Tim were the but adolescents; of the four couples arrested, two had younger children, while some other had adult sons. Fifty-fifty so, the other families were probably the merely people in the world who could even begin to understand their surreal situation.

Bezrukov and Vavilova constitute themselves back in a very unlike Russia from the one they had left. The oldest of the agents had been retired from active espionage work for a decade, Alex says, and barely remembered how to speak Russian. The group were told they would no longer piece of work for the SVR, merely jobs were found for them in state banks and oil companies. Anna Chapman was given a television series and at present has her own fashion line. Bezrukov was given a job at MGIMO, a prestigious Moscow university, and has written a book on the geopolitical challenges facing Russia.

Tim and Alex were given Russian passports at the end of Dec 2010; suddenly, they became Timofei and Alexander Vavilov. The names were "completely new, foreign and unpronounceable for usa", Tim says. "A real identity crunch," he adds with a hint of bitterness. Unable to render to academy for his terminal twelvemonth, he managed to transfer to a Russian university and complete his caste there, before doing an MBA in London.

Alex was less lucky. He finished loftier school at the British International School in Moscow, but did not want to stay in Russia. He applied to academy in Canada, but was told he would beginning have to use for a new birth certificate, and then a citizenship certificate; only then could he renew his Canadian passport. In 2012 he was admitted to the University of Toronto, and practical for a iv-year educatee visa on his Russian passport. The visa was issued and he planned to depart for Canada on ii September. But four days before he was due to go out, equally he was packing his bags and exchanging emails with his future roommate, he received a phone telephone call from the Canadian embassy in Moscow demanding he come for an urgent interview. The coming together was hostile; in that location were a lot of questions about his life and his parents. The visa was annulled before his eyes, and he lost his university place. Alex has since been rejected for French and British visas. Twice, he has been accepted to report at the London School of Economics, only both times did non become a visa. Eventually, he was able to get a visa to written report elsewhere in Europe; Tim travels mainly in Asia, where many countries can exist visited visa-free on a Russian passport.

The brothers' battle to regain Canadian citizenship is not but about logistics. Moscow is non a city that embraces newcomers, and neither of them feels especially Russian. "I feel like I have been stripped of my ain identity for something I had aught to do with," Alex tells me. Both are keen to piece of work in Asia for the time being, but desire to move to Canada when they feel ready to start families. More than anything, their Canadian identity is the terminal straw they accept left to grasp on to, after so much of the rest of their previous reality brutal away.

"I lived for 20 years believing that I was Canadian and I still believe I am Canadian, null can change that," Tim wrote in his affidavit to the Toronto court. "I do not have whatsoever attachment to Russian federation, I do not speak the language, I do not know many friends there, I have not lived there for whatever extended periods of time and I do not want to alive there."

Everyone who is born in Canada is eligible for Canadian citizenship, with one exception: those who are born to employees of foreign governments. But the brothers' Toronto-based lawyer, Hadayt Nazami, argues that it is ridiculous to apply the provision to their case; the whole point of the police force, he says, is to prevent those who don't have the responsibilities of citizenship from enjoying its privileges.

Ultimately, the courtroom seems to exist operating as much on emotional as on legal grounds, maybe with the Wall Street Journal story about Tim's apparent recruitment at the back of its mind. Only even if the brothers knew well-nigh their parents' activities (and at that place is no hard evidence of this), I wondered what the court expected of them. What is a 16-year-former who finds out he is the child of Russian spies supposed to do? Call the FBI?

Tim and Alex have been through many months of questioning themselves and their identities, and of wondering whether they should be angry with their parents. They don't want their babyhood to ascertain them as they grow older. Many of their close friends know, simply nigh of their coincidental acquaintances don't. When asked where they are from, the default response for both is "Canada".

They remain friends with many people from their previous life in Boston, though Tim says some broke off contact, mainly those whose parents were friends with his parents and felt betrayed.

While they take no wish to live in Russia, both brothers visit Moscow every few months to see their parents. I ask them how hard it has been to keep that human relationship going. Was there a confrontation? Tim and Alex choose their words carefully; they want to appear rational and pragmatic, rather than emotional, it seems. "Of course, at that place were some very difficult times," Tim says. "But if I get aroused with them, it's not going to atomic number 82 to any beneficial outcomes." He admits information technology is sad that, even though he tin now spend time with his grandparents, the language barrier means he will never know them properly. "In terms of family and keeping this whole thing together, it really doesn't work out well when you choose this kind of path," he says, his vocalisation trailing off wistfully.

Alex tells me that he sometimes wonders why his parents decided to have children at all. "They live their lives like everyone else, making choices along the way. I am glad they had a crusade they believed in then strongly, but their choices mean I feel no connection to the country they risked their lives for. I wish the world wouldn't punish me for their choices and actions. It has been deeply unjust."

A number of times, Alex tells me that information technology is not his identify to judge his parents, just that six years ago he spent a long menstruum wrestling with "the big question" of whether he hated them or felt betrayed. In the end, he came to 1 conclusion: that they were the same people who had raised him lovingly, whatever secrets they hid.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/07/discovered-our-parents-were-russian-spies-tim-alex-foley

0 Response to "Who Was Beyonce's Parents What What Did They Name Their Baby"

Post a Comment